The Living Lab project (Sote Hyte Living Lab – Co-creation in North Karelia) worked together with Aistikanava, a company based in Outokumpu, to organise a two-week experiment for the Magic Mirror equipment in spring 2023. During the first week, the equipment was tested in Joensuu in Validia, a service provider of sheltered housing under the Act on Disability Services and Assistance. Clients at the day centre were able to try the Magic Mirror on several days and give valuable user feedback. Then during the second week, people involved with the Living Lab project and a number of interested students and teachers in the social and health care sector in Karelia and Riveria had the chance to try out the Magic Mirror at several different occasions in day centre facilities and on the Karelia University of Applied Sciences campus.

Multisensory gaming for groups

To plan the Living Lab cooperation, we met with the forepersons from Validia for the first time in December 2022. At that time, we initially discussed doing a small-scale technology experiment to support the functional capacity of clients in a genuine client environment. Negotiations continued throughout the spring while we were looking for suitable technology for the Living Lab experiment.

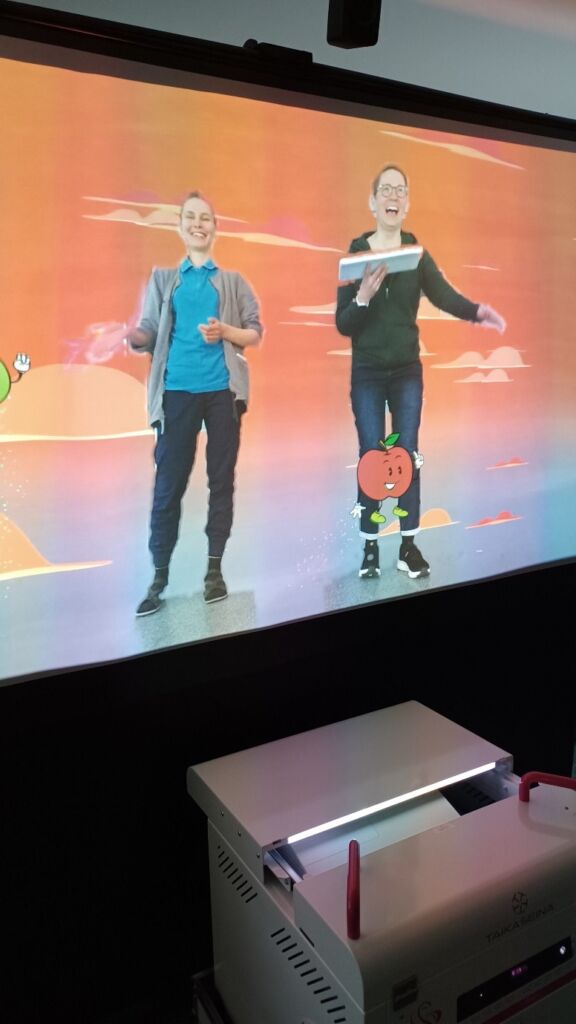

At the beginning of April, we visited the Living Lab project team at the facilities of Aistikanava in Outokumpu with entrepreneur Esko Vihava, and we were introduced to a solution called Magic Mirror. The Magic Mirror™ uses creative and multisensory gaming to not only develop physical engagement but also interaction and communication skills. It aims to find an accessible way for everyone to participate in games. The equipment accommodates 1 to 6 players at one time. No separate controllers are needed for playing; instead everyone can participate equally in the activities by using their body or different parts of it. However, the equipment also enables using gaze, speech, switches, touch, game controllers or mouse and keyboard when necessary. For more information on the Magic Mirror, see the Aistikanava website.

During our introduction visit, we noted that the Magic Mirror applications let participants with different levels of functional capacity work together and play in different environments. We got excited about the idea of testing the Magic Mirror with clients at a day centre facility. With the Aistikanava entrepreneur also interested in working with us, we started planning the actual experiment.

From planning to practical implementation at a quick pace

Implementing a technology experiment in a genuine operating environment with end-user clients requires careful planning. On the other hand, the planning stage itself is not meant to take up an excessive amount of anyone’s time or be a hugely lengthy process, so that there will be enough time for the implementation and evaluation of the experiment as well. First of all, we agreed with the day centre instructor on the storage of equipment, scheduling the experiment and informing the clients about the experiment. In the planning process, we used the experiment plan template used in the VaPa project, a collaborative project of Karelia University of Applied Sciences and the Central Karelia Development Company KETI that concluded in spring 2023. The template had been prepared with the help of the Government’s guide for supporting experiments (Opas kokeilujen tukijalle 2019) and the Association of Finnish Local and Regional Authorities’ starting guide for experiments (Kokeilijan starttipaketti 2017). We used the experiment plan template to prepare shared goals with the day centre instructor.

We set the goal of enabling instructors and clients to familiarise themselves with the new technology. From the instructor’s perspective, the aim was to gain practical experience of using the technology as part of maintaining clients’ functional capacity. Another aim was to test whether the Magic Mirror introduces meaningful and different kinds of activities to the day centre and to see how it facilitates social situations in a group.

In the last week of April, we tested the Magic Mirror during the day centre group activities at Validia on four weekdays for about one hour at a time. Eight of the day centre clients were brave enough to test the equipment in practice. There were a total of about twenty introduction visits during the week. Some clients did not necessarily participate in actually using the equipment, but they were still involved by following along what others were doing. Different contents were tested in various ways. The most popular content ended up being functional games where the players saw themselves within the game world. One client commented: “it was better when you could see yourself in the game world, because it made it easier to know where your arms or legs were”. They said it felt like looking in the mirror. One day, we tested some relaxing content, and people thought it was a pleasant alternative to other options like music.

Clients involved in the experiment gave the following feedback: “Different kinds of exercise and new activities”. One said that “we could use this from time to time”. Together with the testers, we also found that it was possible to use the equipment while in a wheelchair, even if you could not move your body much otherwise. Another comment was that “the best programs were the ones where you have to do something (move or reach for something with your arms or legs)”.

We also received feedback on ideas for developing the Magic Mirror equipment. From the perspective of the day centre instructor, the Magic Mirror allows clients do things that are pleasant and different. Testing the technology was also rewarding and the clients enjoyed the experiment week. The implementation of the experiment also benefited from the technology being easy to use. The Magic Mirror brought repetitive movement and activities to the day centre that people would not usually do, for example if they were in a wheelchair. It was also interesting to see how the Magic Mirror experiment generated pleasant conversation when the equipment was being used. This means that solutions such as the Magic Mirror could offer communality and increase interaction through different group activities.

At the end of the experiment week, we organised a workshop for working life partners at the premises of the Validia day centre. Five people joined in as collaborative working life partners. They got to hear clients tell about their experiences of using the equipment and the observations made by the instructor. Everyone also had the opportunity to try out the equipment themselves. The participants were not familiar with the equipment, so experimenting with the new technology was felt to be useful. During the workshop, participants considered the possibilities of the Magic Mirror for different target groups and operating environments. One clear advantage of the Magic Mirror is that it is suitable for people with different functional capacity and for people of very different ages, children and older people alike. Setting up the Magic Mirror and moving it around is relatively easy, which makes it easy to move from one unit to another.

Campus week saw a steady stream of testers

The Magic Mirror was tested on three different days on the Karelia University of Applied Sciences campus at the beginning of May. We organised a pop-up event where anyone could stop by at any time or stay for a while. There were a total of 104 participants who were mainly students and teachers in the social and health care sector at Karelia and Riveria. Some international students also participated, so the project staff had the opportunity to practise instructing the use of the equipment in English.

Feedback was collected with a QR code from the participants at the working life partners’ workshop and the Karelia experiment week. The survey received 39 responses. We were very curious about how and where the participants had heard about the Magic Mirror experiment. Most of the working life partners, Karelia’s personnel and Riveria’s teachers had either received an email about it or heard about it from someone else. The students at both educational institutions said that they had heard about it from their teachers, and they did mostly come to learn about the equipment during their classes.

Only two people who gave feedback on the experiments had previous experience or knowledge of the Magic Mirror. The majority of the visitors felt that the experiment was useful and that it is important to have opportunities to learn about different social and health care technologies in a versatile way. The majority hoped the experiment would take place at a time that fit their schedules, during classes or as part of everyday work with clients.

Some students were inspired to check out the experiment after seeing an advertisement posted on the wall at the campus, which shows the students’ initiative and genuine interest in using new technologies in the social and health care sector. This led us to think that perhaps we could have more of these kinds of introductions to technology and testing opportunities on campus in the future, even outside classes. Similar events could bring together social and health care students who are particularly interested in technology and who might be interested in joining the Living Lab activities, for example.

Testers’ comments from the campus week:

“A fun and functional innovation!”

“Got sweaty and had fun”

“Very good I like it”

“These Living Lab activities are so wonderful, it’s great to have an opportunity to learn about different technologies!”

What did we learn from the Magic Mirror experiment?

In December 2022, we published an article titled Living Lab – Possibilities for co-creation in North Karelia, where we explained what the Living Lab operating model was about. During the spring of 2023, we have come up with ideas on what Living Lab activities in Karelia mean in practice for the various actors involved in the project, such as local social welfare and health care businesses and organisations and our other partners in the region as a whole. In practice, the Magic Mirror experiment done in cooperation with Validia and Aistikanava is our first larger co-creation process and technology experiment. We started planning the process already at the beginning of the year by looking for partners. As we did not have an existing cooperation network from business and working life at the time, this stage naturally took a while. After we found suitable partners, the planning progressed quite rapidly.

We organised a joint feedback discussion event a few weeks after the experiment. Aistikanava entrepreneur Esko Vihava thought that the planning and implementation process went smoothly. Despite the tight schedule, the practical side of things was coordinated well. Day centre instructor Jonna Tolppanen said that the experiment was a nice thing as a whole. She did not find the experiment stressful because there were people offering guidance and user support for the technology the whole time. Getting information out about the experiment at an earlier time would have been good, even though we managed to make it work on a tight schedule. So we cannot emphasise the importance of communication enough, which is a good lesson learned.

Initially we also meant to involve social and health care students in Karelia and Riveria so that they could practise using the equipment and guiding end-user clients. We had thought that we could fit five students to participate in the client guidance situations at one time, but afterwards, considering the size of the day centre, about 2 to 3 students would have been more optimal. Finally, we concluded that getting students involved would have required a longer process, so we were not able to bring students and end users together this time.

With regard to the future, however, we now have good ideas on how to do the experiment in cooperation with students. It is important for students to be introduced to different solutions that are already in use or being planned for the social and health care sector. This should happen already during their studies, both at the upper secondary level and at universities of applied sciences, by introducing solutions that are as diverse as possible. Technological experiments could offer more opportunities for practising actual guidance situations and create a better understanding of how to utilise technology in social and health care client work.

It was apparent from the students’ comments that they liked having new opportunities to learn about technology. They also appreciated having some variety between long lectures by getting some exercise and experimenting with technology, so it could be appropriate for recess activities. In addition, the students felt that there needs to be more opportunities for being introduced to technology, as it may not be possible to learn about or experiment with technology out in the field in a way that is versatile enough.

Low-threshold opportunities for experimenting with new technology are necessary

From the perspective of the Living Lab project, the experiment was a unique learning process. We immediately noticed that it is important that someone is always there to give guidance during the experiment and help with using the equipment. It is not enough to set up a new piece of technology in a corner somewhere. In addition to testing the actual technology, it is important to engage in dialogue with the people learning about the technology on how the solution will be adapted to different target groups and users. Of course, we still need to have dialogue from different perspectives with clients, social and health care professionals, teachers and students. The perspectives of availability and accessibility are perhaps more emphasised with clients, whereas the perspective of guidance is particularly central with professionals and students in this sector.

All in all, the experiment was successful and reinforced the idea of doing technology experiments with Living Lab in the future as well. For example, we could use low-threshold pop-up events to visit different parts of the region and offer new experiences with digitalisation to people of all ages. At the same time, social and health care students could practise guidance situations using new technological solutions. From the perspective of working life partners, experiments of this type offer different networking opportunities and, above all, ideas and input for developing the operations and services of their business or organisation through technological solutions.

Authors:

Jaana Kurki, Project Manager, Karelia University of Applied Sciences

Suvi Leppänen, Project Specialist, Karelia University of Applied Sciences

The authors work in the Sote Hyte Living Lab co-creation project in North Karelia

Sources:

Aistikanava. www.aistikanava.fi

Leppänen, A., Ripatti, H. & Jäppinen, T. 2017. Kokeilijan starttipaketti. Association of Finnish Local and Regional Authorities. https://www.kuntaliitto.fi/julkaisut/2017/1867-kokeilijan-starttipaketti 2 June 2023

Aarninsalo, L., Hokkanen, V., Vesterinen, M. 2019. Kokeiluluotsi – opas kokeilujen tukijalle. Publications of the Prime Minister’s Office 2019:1. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-287-685-0 2 June 2023